After reading about the nutritional value of dates for the brain, I headed to the nearby farmer’s market where they sell everything you can imagine from the Middle East as well as other international foods. At the dried fruit section, I studied the different kinds of dates. Medjool and deglet were familiar. Then I saw a box with three kinds of dates I had never heard of: piarom, zahedi, rabbi. They even looked a bit different. Tired of the same ole stuff to eat, I bought the box then went home and decided to research the origin and characteristics of each one.

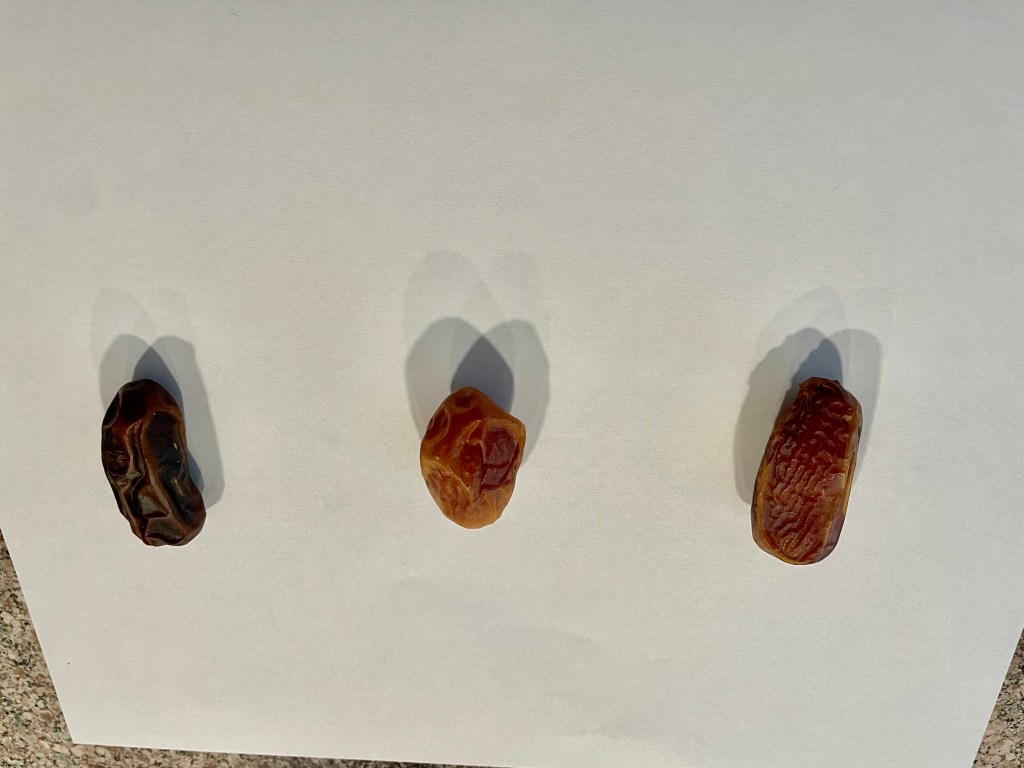

Unlike medjool dates which are considered wet, these three are considered semi-dry. The piarom are grown primarily in southern Iran. Some depending on exact origin and harvest are one of the most expensive dates in the world. They are longer and thinner and a dark chocolate color so often referred to as chocolate dates due to both color and flavor. Another common name for them is maryami. The pits are smaller and so there is more flesh per date. They contain less sugar (lower glycemic) than the wet dates like medjool.

Zahedi dates even look really different. They are shorter, a bit fatter, and golden colored. The pit is easier to remove than most dates too. They have less sugar content than most other dates and therefore can be eaten in moderation by diabetics. They are primarily grown in Iraq and Iran but some are grown in certain areas of North Africa and Asia.

Although the majority of rabbi dates are grown in Pakistan, their origin is Iran. They too contain less sugar than wet dates like medjool. They are reddish brown and usually a bit fatter than piarom dates. Their flavor depends on the soil and the weather conditions under which they are grown. Generally their flavor tends to be caramel-like and nutty.

Like most dates, these support gut health and provide electrolyte balance due to high levels of potassium and magnesium. One big advantage is their lower sugar levels. In addition to the above, like all dates they contain high levels of polyphenols. I will buy them again.

On the left is piarom, then zahedi, and finally rabbi. Some of the zahedi are very light colored.